Today I visited another site of last year’s Liverpool Biennal: The Oratory. It was closed and so the only photographs I can share are of the outside. (And it goes without saying that if I could show you the inside, the contemporary artworks displayed there last year are long gone).

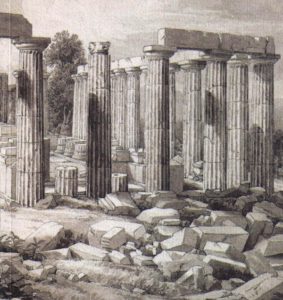

Built on the grounds of the Anglican Cathedral in 1829, The Oratory was a neoclassical building designed by John Foster. The son of an architect, he first had ambitions to be a painter and he joined part of an international group of artists and architects to excavate the temple of Apollo at Bassae. In a letter to his father, dated September 7th 1812, Foster describes the frieze of the temple depicting the battle at the wedding of Pirithous and Hippodamia, including Theseus grappling with the centaur Eurythion (the suject of the sculpture that I had recently seen in Victoria Square Park in Athens). In the same letter, he also describes the procurement and then removal of the frieze of the temple, as well as including some of his sketches.

assisted by two hundred labourers, which number we were obliged to have, owing to the great weight of the stones which it was necessary to remove, and also from the want of machinery, the effect of which it was necessary to supply by manual strength. I enclose you sketches of part of our newly acquired collection.

Foster made two copies of his sketches of the temple, one for his own father and one for the father of his colleague on the excavation, Charles Robert Cockerell. Today the British Museum houses one copy (where I visited on Friday, while in London) and the Gennadius Library in Athens (where I was last Tuesday).

Standing before the close Oratory – this building designed by a painter who was instrumental of the removal of the Bassae Sculptures (otherwise known as the Phigaleian Frieze) – the violence of both the subject of the frieze and their removal was covered by the serene silence of the closed building.

Last year, The Oratory housed a selection of works at the Biennial, two of which directly relate to the story of the building’s architect. The central work in The Oratory was the video Rubber Coated Steel by Lawrence Abu Hamdan. In 2014 Abu Hamdan was asked to work on audio files that recorded the shootings of two Palestinian teenagers Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher on the West Bank, proving that they were shot by real bullets and not rubber ones. Accompanied by a fictional transcript of the trial – which appears in the video as subtitles, sometimes crossed-through, this forensic use of sound demonstrates the acute tension between deadly force and the problem of listening in contested territory. When I first heard of this work as part of the Ancient Greece episode of the Biennial, I was unsure how to make the connection. Yet the context of the building, with the story of Foster’s sketches and their witness to the removal of the ancient frieze, shows how different kinds of violence can be silenced and smoothed away. The other work that makes more direct reference to the neoclassical building, especially as it now houses a collection of ancient sculptures, is by Oliver Laric. His Sleeping Shepherd Boy, 2016 was a 3-D scan of a sculpture from Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery by John Gibson. As part of the ‘Software’ episode of the Biennial, Laric has made available data from the scans to be accessed for free at www.threedscans.com. This digital-based method of copying and distribution contrasts with older methods of casting and copying that had the potential to damage the original works. Furthermore, these processes highlight the relationship between two main modes by which antiquity was brought to British audiences in the 19th century: the plunder and sale of original antiquities and the neoclassical copying of Classical architectural model. While the violence of the former is well acknowledged, the latter still needs to be negotiated as part of the symbolic debt imposed on Modern Greece for their Classical past (as explored in Johanna Hanink’s recent book The Classical Debt).

Standing outside the closed building today and thinking back to these works from last year’s Biennial and these shared ideas of silence and violence, I was drawn to the tranquility and lush greenery of the cemetery beneath. St. James’ Cemetery, also designed by James Foster, and also designed as a copy (according to the model of Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris).

brilliant