[Minus Plato is undergoing some technical difficulties with image uploads so I apologize for the scarcity of pictures to accompany this post. I hope to have this rectified before tomorrow]

When I woke up this morning I had a somewhat modest plan for the day: to visit the Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA) by way of some minor ancient sites.

As with EMST, I was inspired by the stories the documenta 14 curators told about the building (a former textile factory) and how the work shown there had to intervene and extend its earlier history as well as its current role as an art school. (One work that did this most explicitly was Allan Sekula’s School is a Factory (1978-80)). In terms of connecting weaving and learning, the main emphasis was less on the exhibition space itself as on the aneducation project occupying the old library area. The name aneducation is described as follows in terms of how the word is heard as much as read:

A neologism sitting somewhere between anarchy and pedagogy, aneducation rolls off the tongue when spoken, becoming again something else. Depending on which voice or voices breathe it – how loud, how osft, how long – aneducation is embodied differently in the world. A trickster term: listeners cannot know ho aneducation is spelled, leaving space for productive misinterpretation. Indeed the program is less an attempt at a curriculum than a cacophany, a chorus of voices that not only speaks but listens, shifts doubts, and dreams. It is a mode for unlearning, or, conversely, a nourishing act, a warm gesture that reaches out to the possibility of learning otherwise.

When I finally arrived at ASFA in the mid-afternoon, this reactivated library was my first port of call. I found that this emphasis on listening rather than reading became materially apparent as lines of metal bookshelves contained headphones, hanging there where books used to be. In addition, there were a series of spaces devoted to screenings of a collection of short films (on the theme of ‘Transport’) as well as work spaces. Of course, books were still present, but they scattered and acutely positions as they were being activated in other ways, rather than sitting, docile and crowded on the shelves.

But I am getting ahead of myself, before we can reach the nourishing space of the ASFA library and aneducation, let us retrace our steps back to earlier in the day.

On leaving my hotel, little did I know the adventure I would have and the sights I would see on my way to my destination. As I walked towards the Acropolis, I drifted past the Library of Hadrian and the Roman Forum, and decided that I wanted to engage with some of Athens’ extensive Roman era buildings. At the same time, thinking about the central theme of immigration, migration and displacement in documenta 14, I was also curious about how this could be squared with the ancient Athenian claim of autocthony (the myth that they were born literally from the earth) as grounding their greatness. (This was a topic that was curiously absent in Johanna Hanink’s book The Classical Debt that I wrote about a couple of days ago, specifically her chapter on how Classical Athens developed its ‘brand’). Another way to put this question is, how did Athenians stake their claims on their city during Roman rule?

One answer came at the first site I visited: the library of Pantainos. Situated between the Roman Forum and the Stoa of Attalos in the Agora, and facing the Panatheniac Way, this library was built in the early years of the emperor Trajan’s reign (between 98-102 CE) by an Athenian called Titus Flavius Pantainos.

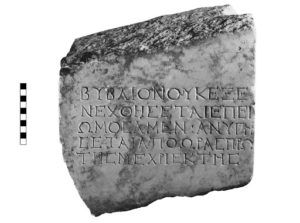

One of the library’s inscriptions, written on a marble herm shaft found in the area, lays down the rules for readers:

No book is to be taken out since we have sworn an oath. The library is to be open from the first hour until the sixth.

Yet since there are signs to additions to the building, there is a suggestion that it doubled as a philosophical school of Pantainos’ father, Favius Menander. Further evidence for this comes from the main inscription:

To Athena Polias and to the Emperor Caesar Augustus Nerva Trajan Germanicus and to the city of the Athenians, the priest of the philosophical Muses, Titus Flavius Pantainos, the son of Flavius Menander the diadoch [head of school], gave the outer stoas, the peristyle, the library with the books and all the furnishings within them, from his own resources, together with his children Flavius Menander and Flavia Secundilla.

The phrase ‘philosophical Muses’ is very intriguing and one way to understand it is to see it, along with the dedication to both Athena Polias and the city itself, as a statement of local pride in the ancient history of the city as a hotbed of philosophical activity, institutions and leaders. It also provoked my choice of the next site I would see as I walked to ASFA (although you could hardly say it was ‘on the way’): the monument of Philopappos on the Mouseion hill. There was something exhilarating about walking up to the Acropolis amid the throng of tourists only to turn the opposite direction and enter into the tranquil park of what is now called Filopappu Hill after the monument at its peak. On reaching the top of the hill, with a breathtaking view of the human bees buzzing around the Parthenon, there stood the monument I had been searching for.

When writing about his journeys through Athens and Attica, Pausanias had described the hill and the monument as follows:

The Mouseion is a hill within the ancient circuit of the city, opposite the Acropolis, where they say that Mousaios sand and, dying of old age, was buried. Afterwards a monument was built to a Syrian man.

This blunt description (obviously taking on an intense resonance here and now with the Syrian war and the resulting refugee crisis) is fleshed out by the inscription on the memorial monument itself, which is written in Latin and describes the person responsible for this building as:

Caius Julius Antiochus Philopappos, son of Cius, of the Fabian tribe, consul, and Arval brother, admitted to the praetorian rank by the Emperor Caesar Nerva Trajan Optimus Augustus Germanicus Dacicus.

The addition of names to Trajan’s title date the monument to later in his rein (114-116 CE), while Philopappos’ name ‘Antiochus’ connect him to his Syrian heritage. In fact, part of the carved frieze on the monument shows Philopappos in a consular procession in a chariot, while the niches show his connection with the royal Syrian line – Kings Antiochos IV of Commagene and Seleukos Nikator. Given that Philopappos’ grave was allowed within the city, it figures that he was an important benefactor to the city and most became an honorary Athenian citizen, unlike the local philanthropist Pantainos. So within a few years of each other, we have these two buildings – a library and philosophical school by a native Athenian and a funeral monument for a Syrian benefactor of Athens place conspicuously on the hill of the Muses.

As I stumbled down the hill, tried to tease together the connections between these two men and their monuments. It was then that I came across the shrine to the Muses, that gave the hill its name before Philopappos.

I kept thinking about those ‘philosophical Muses’ in the library beneath the hill and what, if any, connection there was with this modest shrine. Of course, when we use the word ‘museum’ we are connecting the display of art works with the more expansive places like the Museion of Alexandria, with its famous library. Closer to home, Plato’s Academy, in the site of which there was already a shrine to the Muses, fits the description of an ancient Museion. I thought of Plato again as I peered into the small space and discovered – to my complete joy – a hive of bees in the roof. While bees were important metaphors for poetic creativity in Greek and Roman literature, they were especially associated with the Muses. Varro the Roman antiquarian called them the birds of the Muses and Plato’s Ion imagines poets as bringing us the honey of the Muses like bees. (In Plato’s ancient biography, sometimes he is described as having bees sitting on his lips as a baby!).

Mesmerized by my encounter with the bees of the Muses, I began my descent and my circuitous journey to ASFA. Yet on my way down the hill I came across some works from documenta 14. First of all the powerful and dramatic marble tent by indigenous Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore, which, like Philopappos’ monument, faced across the hill, provocatively staring down the Parthenon on the Acropolis.

Moving down the hill there was a small pavilion next to the Church of Saint Dimitrios Loubardiaris in which works by mother and daughter artists Elisabeth Wild and Vivian Suter were housed. Suter’s large colorful canvases were not hung, however, but were blowing gently in the breeze from washing lines. Perhaps it was my encounter with the bees of the Muses, but I found all of these works intensely poetic and this feeling increased when I discovered that the documenta curators had also included in the list of works the network of paths created by architect Dimitris Pikionis and his students between 1954 and 1957 that I had just been walking on. In many ways this experience on the hill across from the Acropolis was the most subtle yet convincing proof yet during my visit to Athens that my project of connecting the Classical and Contemporary Art has an important and vital place in documenta 14.

This was proved all the more the case when I arrived, after several wrong turns and completely exhausted, at ASFA. As I recovered in the old library space of aneducation, how libraries act as schools and how the libraries and schools can be shrines to the Muses, both made tangible sense. At the same time, given the two different Roman Athenians – one from Athens, another from Syria – the way that these spaces of learning and encounter can bring different senses of community and the collective is vital to the aims of documenta 14 (and, I would argue, for the future of the discipline of Classics as well). For example, the way that the exhibition engages with Athens’ main art school is to bring into their vicinity pedagogically-focused art collectives from India, Cuba and Chile. Finally, beyond aneducation, there were exciting moments when the work of readers and Muses I had encountered on the hill, reappeared in the context of the school. There was displayed photographs of and working drawing for Dimitris Pikionis’ paths. Also, the two artists in the pavilion Elisabeth Wild and Vivian Suter were the subject of a specially commissioned film by Rosalind Nashashibi called Vivian’s Garden (which contains a story about bees). To discover these works that I had encountered within the framework of ancient sites and their ideas of the library, the school and the Muses, framed within the themes of education, collective creation and collaboration was a startling and rewarding experience.

Speaking of such experiences, click here to see tonight’s Social Dissonance performance (in which bees appear once more).