In Pythagoras’ speech in the 15th and final book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the vegetarian philosopher of rebirth tells the tale of the phoenix bird (Met. 15. 392-407).

una est, quae reparet seque ipsa reseminet, ales:

Assyrii phoenica vocant; non fruge neque herbis,

sed turis lacrimis et suco vivit amomi.

haec ubi quinque suae conplevit saecula vitae,

ilicet in ramis tremulaeque cacumine palmae

unguibus et puro nidum sibi construit ore,

quo simul ac casias et nardi lenis aristas

quassaque cum fulva substravit cinnama murra,

se super inponit finitque in odoribus aevum.

inde ferunt, totidem qui vivere debeat annos,

corpore de patrio parvum phoenica renasci;

cum dedit huic aetas vires, onerique ferendo est,

ponderibus nidi ramos levat arboris altae

fertque pius cunasque suas patriumque sepulcrum

perque leves auras Hyperionis urbe potitus

ante fores sacras Hyperionis aede reponit.

(There is one bird which reproduces and renews itself: the Assyrians gave this bird his name—the Phoenix. He does not live either on grain or herbs, but only on small drops of frankincense and juices of amomum. When this bird completes a full five centuries of life straightway with talons and with shining beak he builds a nest among palm branches, where they join to form the palm tree’s waving top. As soon as he has strewn in this new nest the cassia bark and ears of sweet spikenard, and some bruised cinnamon with yellow myrrh, he lies down on it and refuses life among those dreamful odors.—And they say that from the body of the dying bird is reproduced a little Phoenix which is destined to live just as many years. When time has given to him sufficient strength and he is able to sustain the weight, he lifts the nest up from the lofty tree and dutifully carries from that place his cradle and the parent’s tomb. As soon as he has reached through yielding air the city of Hyperion, he will lay the burden just before the sacred doors within the temple of Hyperion.)

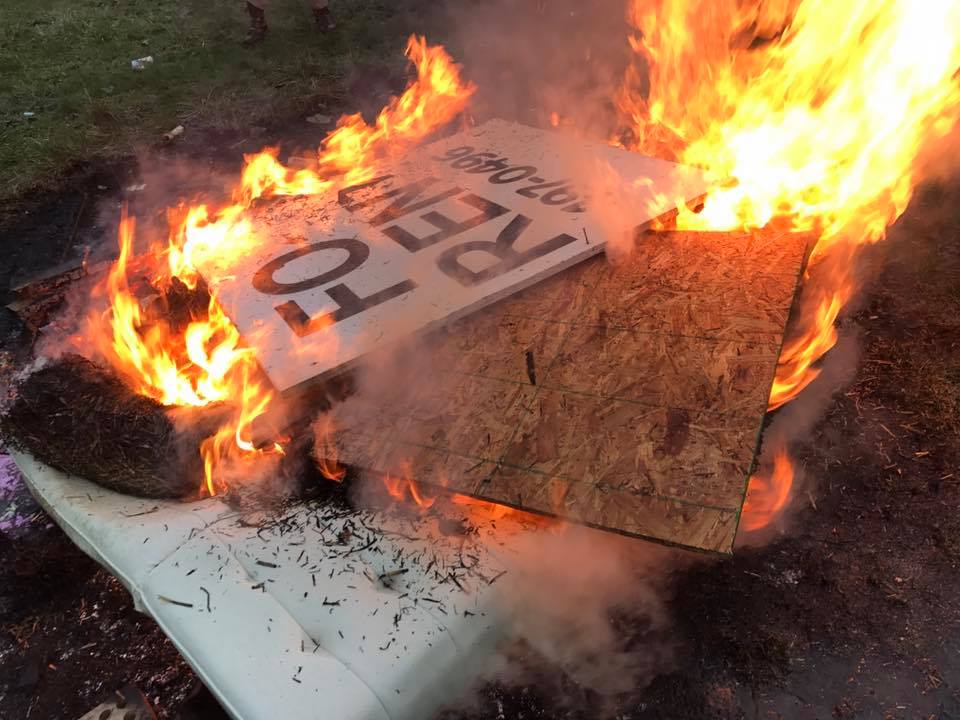

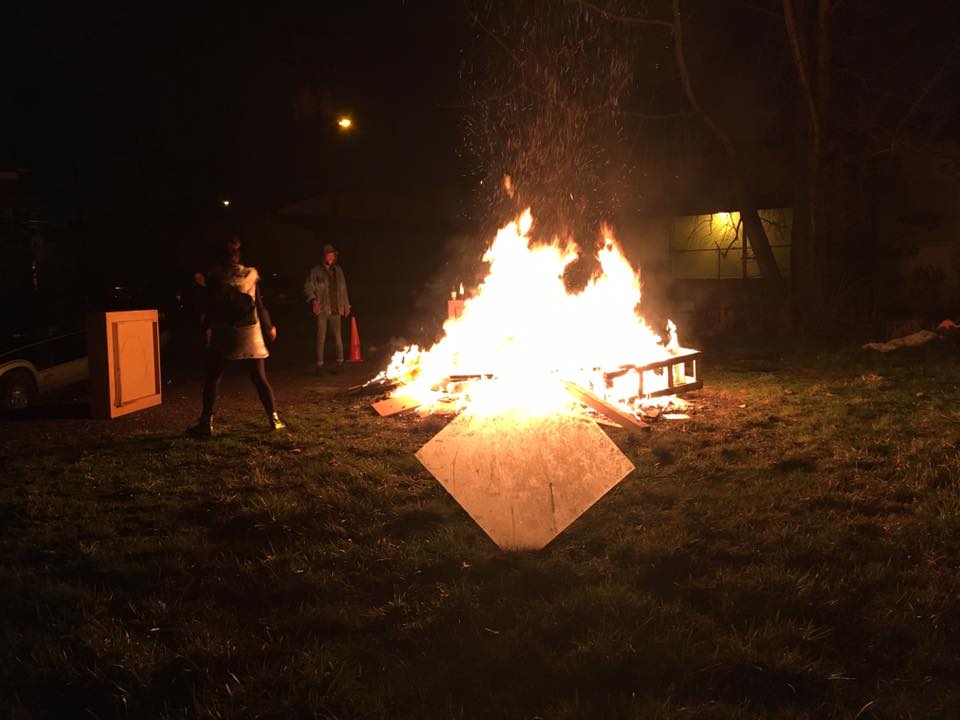

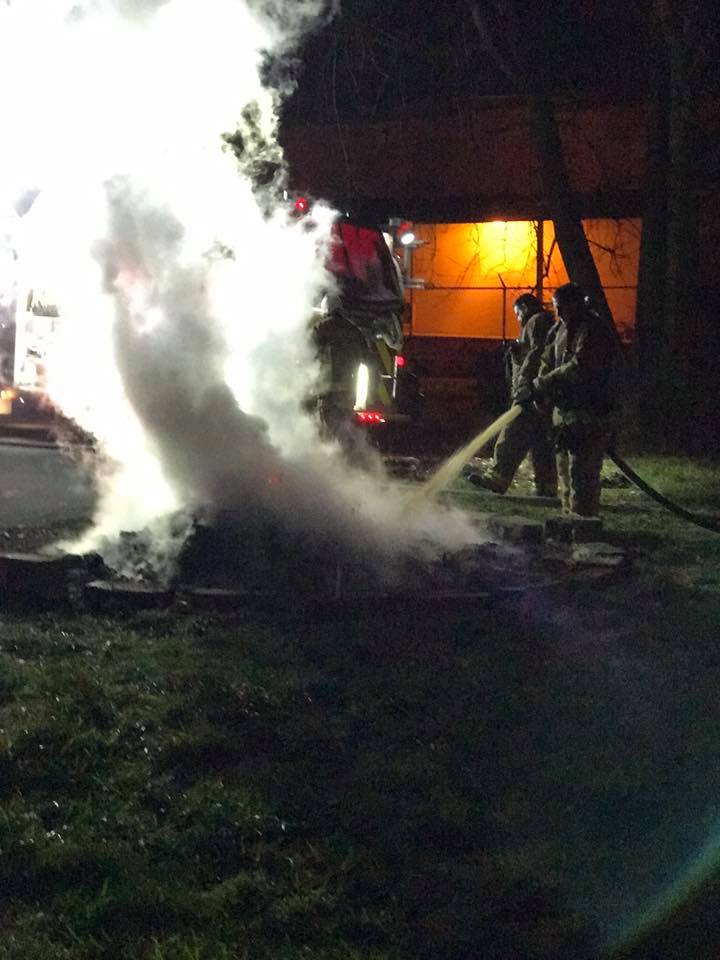

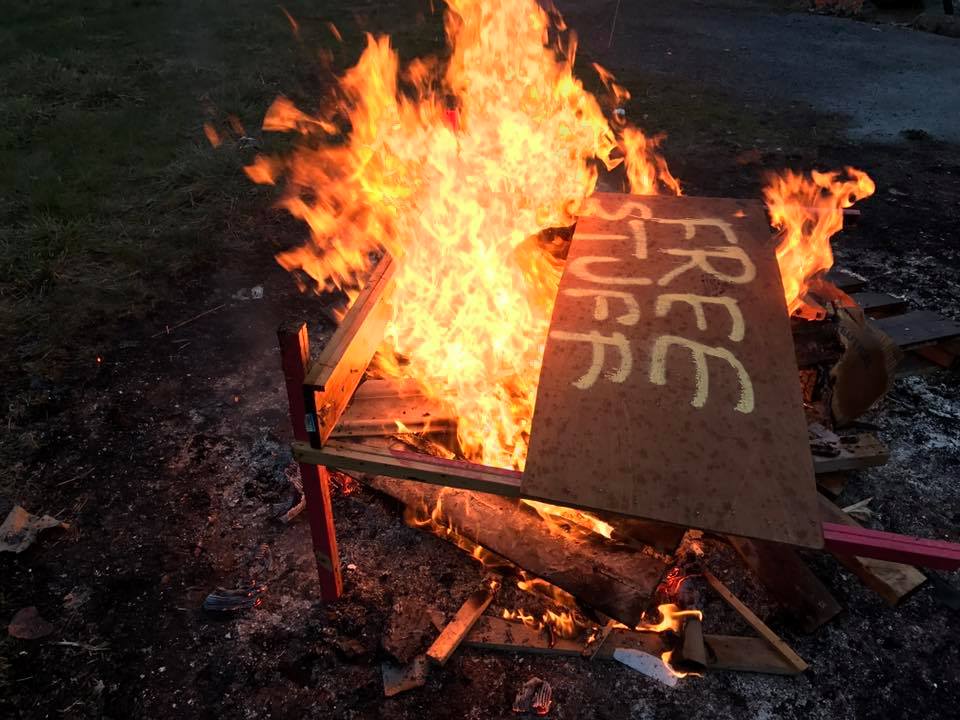

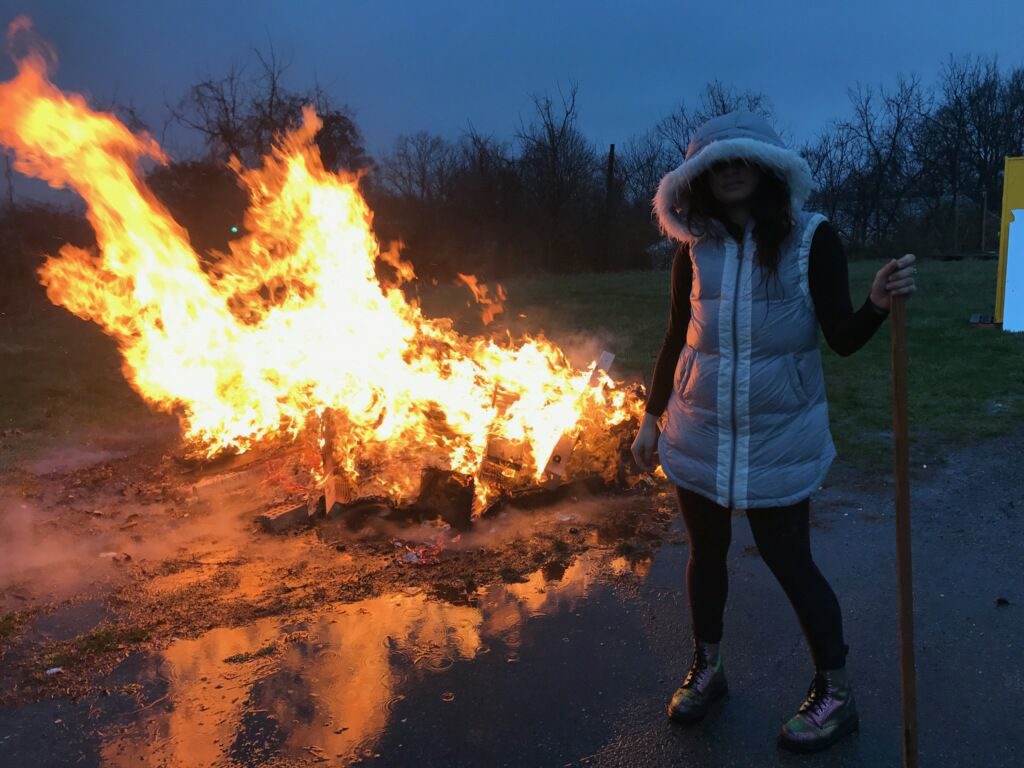

One aspect of Ovid’s version of the myth that I have never really thought about before is the pivotal role of its nest in its fiery transformation. It is not only the Phoenix’s attention to the process of building its nest that struck me, but also how the new-born bird, in its piety (pius), brings its nest as both their own cradle and also their dead parent’s tomb on its journey to the city of the father of the Sun, Hyperion. As a Classicist, this description obviously reminded me (and I am sure Ovid meant to evoke) the image of the journey of pius Aeneas, who founded Rome out of the smouldering ashes of Troy, carrying his father and leading his son through the flames of his burning city. Now, however, Ovid’s Phoenix and its transitional nest makes me think of the M I N T Collective, who, following weeks of work clearing out their space at 42 W Jenkins and nights of burning the remnants from their old nest, are embarking on a new nomadic phase. On this day, amid the news of the attack on London’s Parliament and all the other destructive aspects of our burning, rented world, the fire that connects the Phoenix and the M I N T Collective are both equally potent images that we need to keep close to hand. (Thank you to all the MINT members who shared their photos of their flaming rebirth!)

“Audentis fortuna iuuat.”

– from the Aenied by Virgil.

Thanks for the information about phoenixes, it was a successful article.