Following Louise Lawler for Art after Modernism, the New Museum and MIT series ‘Documentary Sources in Contemporary Art’ continued to commission artists as photo editors for their future volumes. Barbara Bloom selected the images for the second volume – Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writings by Contemporary Artists, while John Baldessari included a photographic sketchbook for the third volume – Discourses: Conversations in Postmodern Art and Culture.

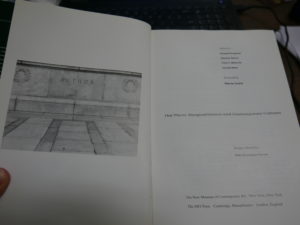

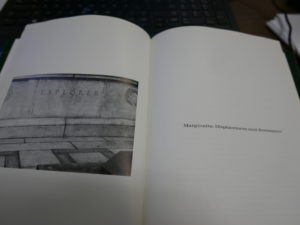

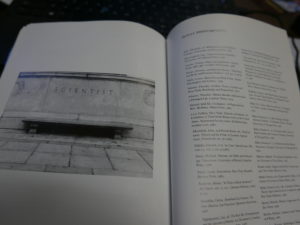

For the fourth volume – Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures – the task fell to Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The majority of the artist’s intervention in the volume consists of two projects. The first Untitled (I Think I Know Who You Are), 1989 is interspersed throughout the book and depicts a section of a building and pavement, with various identifying words inscribed in the wall – e.g. AUTHOR, STATESMAN, SCHOLAR, etc. (They actually come from the American Museum of Natural History).

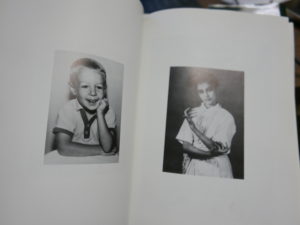

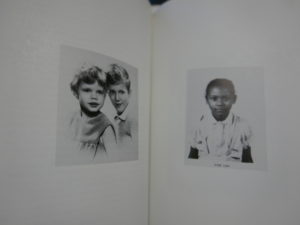

As counterpoint to the grandiosity of what one of the book’s editor’s – Russell Ferguson – dubs these photographs’ ‘mythic classifications’, Gonzalez-Torres also includes two self-contained sections within the volume of childhood portraits of the authors of the various essays in the book (Also included Gonzalez-Torres himself, as well as Julie Ault, who contributed a visual work – Torture on the Moon – and who was Gonzalez-Torres’ fellow member of Group Material).

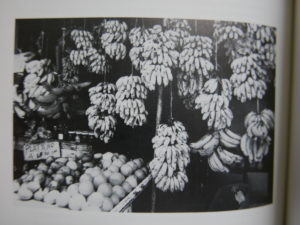

Both extended interventions in Out There are accompanied by more localized visual commentaries on the essays. The one that stood out for me was the found postcard image (which the credits describe as having the title ‘Exuberant Caribbean’) of a market fruit-stall with clusters of hanging bananas.

Gonzalez-Torres used this image to introduce Helene Cixous’ essay ‘Castration or Decapitation?’. At the beginning of the essay, Cixous juxtaposes two ancient stories – one about the Greek gods Zeus and Hera and the judgment of Tiresias as to whether women or men experience more sexual pleasure, and the other from the Chinese author Sun Tse’s The Art of War, wherein a general was challenged to make an army out of the king’s 180 wives, and when they all started laughing, he beheaded the two female commanders and that turned the whole army into soldiers. What have these two stories go to do with the hanging bananas? Of course I am not claiming a literal correspondence between the image and the text, but I was immediately struck by how the banana could symbolize the phallus, while the bunches of bananas could symbolize the decapitated head of Medusa (a figure whose laughter Cixous would write about elsewhere). In addition, the relationship between the single phallic banana and the bunch-as-head is present the Tiresias myth, not only in the accounting of his seven years as a woman and seven years as a man, but also in his answer to Zeus and Hera, quantifying the amount of sexual pleasure that women experience – “if sexual pleasure could be divided up into ten parts, nine of them would be the woman’s”. Also, given the significance of laughter in the Chinese tale and Cixous’ argument about female jouissance, the figure of the banana in comedic situations (as that slippery prop of slapstick) acts as a stand in for the joy of sexual pleasure, as experienced by Tiresias as a woman.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly for Gonzalez-Torres, the postcard from an exotic location, the Caribbean market stall and its platanos, can intervene in a discourse that utilizes the mythic otherness of ancient Greece and China to explain certain psychoanalytic and cultural theories. By inserting his ‘Exuberant Caribbean’ into this context, the Cuban-born Gonzalez-Torres is generating his own mythic classification. Like Tiresias, Gonzalez-Torres’ judgment in selecting the images for a volume about marginalization, not only puts his own identity under scrutiny, but also gives him a power to transcend the binary of male/female, castration/decapitation by highlighting the stereotype of the Caribbean exuberance (jouissance) of his Cuban picture postcard. The simplicity of the postcard, therefore, works somewhere between the monumental mythic classifications of the Untitled series and the playful portfolios of childhood photographs, to demonstrate Gonzalez-Torres’ own version of Tiresias’ impossible dilemma as the scrutinized photo editor of the project.