Working in the Wexner Heirloom Cafe, sitting with my laptop as I prepare for classes and answer emails, also means that I am lucky enough to be interrupted by compelling conversations about contemporary art. It just so happened today that I was reminded of the ancient myth of the apple of discord by two completely different conversations.

The first conversation, with a curator and collector, was focused on an exciting future exhibition at the Columbus Museum of Art and involved our shared admiration for a work in their permanent collection (but not shown for many years): Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s work 20 Ways to Get an Apple Listening to the Music of Mozart.

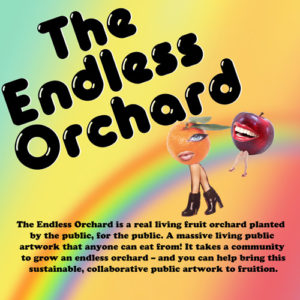

Then, minutes later, in another conversation, I was informed by an educator at the Wexner about a Columbus iteration of the Los Angeles-based artists David Allen Burns and Austin Young, founders of Fallen Fruit. As part of their project Endless Fruit, roughly 40 trees (including apple trees) will be planted in a location in the South Side of Columbus and will be called South Side Fruit Park as a community engagement and adoption project (For more info, go here).

Then, minutes later, in another conversation, I was informed by an educator at the Wexner about a Columbus iteration of the Los Angeles-based artists David Allen Burns and Austin Young, founders of Fallen Fruit. As part of their project Endless Fruit, roughly 40 trees (including apple trees) will be planted in a location in the South Side of Columbus and will be called South Side Fruit Park as a community engagement and adoption project (For more info, go here).

The apples of these two conversations – the one at the centre of the Kabakov installation and those to be grown, picked and eaten in the Fallen Fruit project – grow closer together when, failing to get back to work, I read online about another, earlier Kabakov project that combines the singular apple of discord with a vision of a collective play. Here is the description of the work called The Golden Apples.

Directly after entering the park, the viewer sees a large bronze woven basket in the center of the lawn on the green grass. Apples are being gathered in this basket after the harvest. And the basket really is half-filled with apples, many other apples are lying all over the place near the basket on the grass. The apples are large and gilded on the outside, which makes them stand out clearly against the green grass of the lawn. The question involuntarily arises: the significance of this basket is unclear, why are some of the apples inside and the rest are outside?

But when the viewer lifts his head, he sees that there are three male figures clearly visible against the bright sky in the tops of the three trees closest to this spot. Each of these figures is in a vivid dynamic pose, and in each one’s hand is a golden apple just like those in the basket and lying near it.

Despite the distance between the basket and the three figures, the viewer immediately ‘grasps,’ understands the connection between them. Furthermore, this ‘rupture’ in two places in the installation forms the fundamental plastic ‘intrigue’ and works to embody its subject. It functions like a riddle with an unexpected solution: here is why some of the apples are on the grass and others are in the basket; it’s because someone has managed to hit the basket, while others have missed.

The intrigue of this work leads me back to the secret of the future exhibition at the CMA. Perhaps by then the apple trees on the South Side will be bearing fruit.