I have just returned from Lawrence, Kansas, where I delivered the keynote address at the Oliver Phillips Latin Colloquium at the University of Kansas. (I am grateful to all the faculty, teachers and students who attended and for making it a memorable visit). My talk was called ‘The Latin Lessons of Contemporary Artists’ and I discussed the use and abuse of the Latin Language by a range of artists including Mary Kelly, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Ann Hamilton and Wallace Berman.

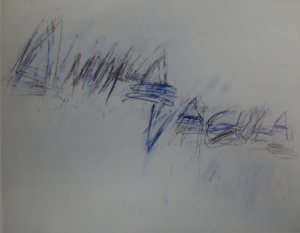

Building on the tension that Rosalind Krauss pointed out in interpretations of Cy Twombly’s work in her essay ‘The Latin Class’, between sober engagement with the Classical tradition and schoolboy doodlings of the name ‘Virgil’, I looked at how artists (including Twombly) turned to the Latin language to comment on both the expansive, rich history of the language, as well as its potential for manipulation and word-play within the language and its visual representation.

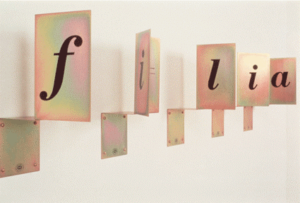

I discussed how some artists negotiated the use of single Latin words for titles of works, such as Ann Hamilton’s series lignum or corpus and Mary Kelly’s interim, with it’s 4 sections – corpus, pecunia, historia and potestas.

For the former the rich semantic range of a word can take on an immersive environment, while the latter shows the distancing potential of Latin for concepts with too-familiar usage.

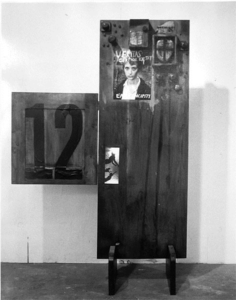

I also showed how some artists embraced a range of approaches to Latin, from single words to whole borrowed or invented phrases. Here I juxtaposed Wallace Berman’s role (well, at least his Latin dictionary’s role!) in the naming of the Ferus (Lat. ‘Wild’) gallery, his magazine Semina (Lat. ‘seeds’) as well as the (untranslatable?) Latin phrase in his Veritas Panel

For Ian Hamilton Finlay, Latin may be borrowed from Virgil’s Eclogues and inscribed on stone in his garden of Little Sparta, made up to attack the Scottish Art Council or deconstructed and broken down at the level of the word, such as works based on the Latin word UNDA (Lat. ‘wave’).

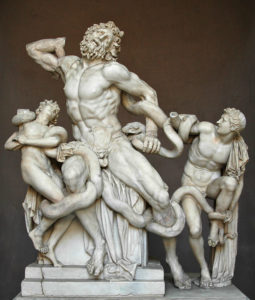

By way of introducing the place of Latin within general discussions of how contemporary artists appropriate and engage Classical antiquity, I opened my talk by recalling a Minus Plato post from 2012 called ‘Collage and the New Laocoon‘. In that post, reacting to both Clement Greenberg’s ‘Towards a Newer Laocoon’ and Roy Lichtenstein’s 1988 painting, I expressed a preference for how Richard Hawkins, Anita Steckel and Leigh Ledare used forms of collage and the manipulated photograph to engage with questions of gender, sexuality and even incest to reconfigure our recognition of the iconic sculpture of the priest, killed by serpents along with his own sons, to foreshadow the fall of Troy.

I returned to this old blog post because it represented two problems with so-called Classical reception studies that I have been wrestling with – (i) the simplistic recourse to art history to understand contemporary engagements with antiquity and (2) the blinkered isolation of ‘Classically-engaged’ works from broader contexts and debates in contemporary art and culture.

These two issues came to the fore for my last year when I stumbled across yet another version of Laocoon: Sanford Biggers’ Laocoon.

Last year I started writing a post on Biggers’s Laocoon, I wanted to make the contrast between how the breathing form of Fat Albert (from the Cosby Show) enacted the contrast that Gotthold Lessing originally made at the opening of his 1766 essay Laocoon: or, The limits of Poetry and Painting between the ‘anxious and oppressed sigh’ of the statue and the ‘terrible cry’ of Virgil’s literary description upon which it was based.

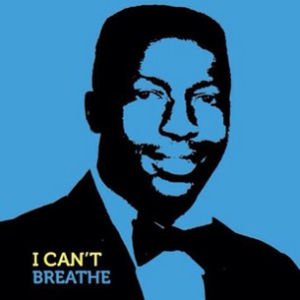

At the same time, the breathing of Biggers’ Laocoon also seemed to alluded to the death of Eric Garner by choke-hold in Staten Island on July 17th 2014, in which case the video footage in which Garner could be heard saying ‘I can’t breathe’ eleven times seemed to shift towards the ‘terrible’ (yet unheeded) ‘cry’ of Virgil’s poetry (Virgil Aeneid 2. 223-224):

clamores simul horrendos ad sidera tollit:

qualis mugitus, fugit cum saucius aram

taurus et incertam excussit cervice securim

(At the same time, he raises terrible shouts to the stars, like the bellowing of a bull that has fled wounded, from the altar, shaking the useless axe from its neck.)

I was reminded now of this aborted blog post of last year, both by the occasion of the Phillips Colloquium, for which I wanted to speak about how examining contemporary artists’ use of Latin may be a way to break free of a purely art historical approach to Classical reception (as exemplified in the appearance of so-many-Laocoons), and also, more disturbingly, by watching the video released by the family of Keith Scott, who was shot dead by police officers in Charlotte, in the airport on my way to Kansas, where the repeated words of Scott’s wife, like those of Garner, were unheeded and ignored with devastating consequences.

But how could I connect the way in which I understood Biggers’ Laocoon as opening out the possibility of this linguistic and literary reception of Virgil in response to the art historical reception of the statue to the use of Latin by contemporary artists themselves?

It was then that I discovered William Pope. L’s 2015 film Obi Sunt. Shown as part of his exhibition Desert at Steve Turner in Los Angeles, Obi Sunt juxtaposes images from a photo book of the 1906 epic boxing match between Joe Gans, an African American, known as “The Master”, against Oscar “Battling” Nelson, with images of the artist, carrying one of his shoes and with a white towel over his head, stumbling through the landscape of Goldfield, Nevada, where the legendary boxing match took place over 100 years before. The title of the work changes the Latin phrase ubi sunt which, in its complete formulation (ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt – ‘where are the ones who came before us’) expresses ideas of nostalgia and loss in a way that is very fitting for Pope. L’s reminiscing about the Gans’ fight. However, at the same time, the subtle change to this Latin phrase (from ubi to obi), marks a resistance to its simplified version of memory and, half-way through the film, becomes the source for the voice over breaking down the very language of nostalgia:

Obi Sunt

Uni Sunt

Obi Sunt

Uni Son

Dust Sky Sun Rust

Dust Sun Sky Lust

Must Rust Sky Fuss

Sun Sky Rust Dust

Tech nologies of Memory

Tech nologies of Memory

Nologies

Nologies

Nostalgia

For an an an

An nother time

Pope.L’s recourse to a deconstructed language of nostalgia, spoken over the image of the artist’s body reaching a literal cross-roads, seemed to me to return us once again to the possibilities set up in Biggers’ Laocoon between body, breath and language. Another of Pope. L’s works has been used as the cover of Artforum in an issue that directly discussed the Eric Garner case, specifically in an essay by David Joselit called ‘Material Witness’.

At the time of the issue’s release, while he praised Arforum for directly addressing the issue of police brutality against black men, Pope. L noted some discomfort about his earlier work Foraging (Asphyxia Version) being used to make a very literal connection to the way Garner was killed (the suffocation of a plastic bag and the choke-hold), marking a distinction between how the magazine can do this and how an artist would choose to ‘represent’ ‘Eric Garner’s death, or Trayvon Martin’s, or Michael Brown’s’.

Is it possible that Obi Sunt was Pope. L’s way of indirectly representing these deaths in his work? If so, the manipulation of the nostalgic Latin of the title offers a different nuance to the discussion of body and breath in Biggers’ Laocoon. The voice over of Obi Sunt is able to control and give context to the representation both of the historic boxing match (against the white-washing of the photo-album), but also of the unrepresentable bodies of murdered black men. If the visual footage cannot persuade courts to prosecute police when the evidence is staring them in the face, and the police cannot heed Garner’s cries that he cannot breathe, nor Scott’s wife’s pleas, then the artist must find some way to represent them and this can happen through the breakdown within language itself. This breakdown starts with the Latin of the title and moves through the film to its voice-over.

My talk at the colloquium, ostensibly aimed to show the range of uses of Latin by contemporary artists who engage with antiquity. But in moving from the body of Biggers’ Laocoon, and its contested breath, to the broken language of Pope. L’s pseudo-Latin title and deconstructed voice-over, I also wanted to find a new way for Classics and contemporary art to work together. When artists move from one type of ‘matter’ (bodies, breath, words) of Black Lives, they bring a complex and challenging aesthetic dimension to the ethical call at the heart of all cries of ‘Black Lives Matter’!

Pingback: OH MY OH MY (Call for Response) | Now Art World