[The exhibition Myths of the Academy opened today and will be on show at the Hopkins Hall Art Gallery at Ohio State University until April 18th. For those of you who cannot make it to Columbus to see the exhibition, here is a taster in the form of the brief essay I wrote for the catalogue.]

There is an anecdote about one of Plato’s students who jotted down all of his teacher’s lectures in the Academy. When he lost all of his written notes on a sea-voyage, he returned to tell Plato that he now knew from experience the truth of the philosopher’s claim that one should not write in books but in men’s souls. While we know very little about Plato’s teaching methods in the Academy, this anecdote offers us some intriguing, if ambiguous, evidence. On the one hand, it locates successful pedagogy not in Plato’s dialogues, but in the master’s oral teachings.

On the other hand, it implies that the dialogues played a pivotal role in the Academy since it was recorded in a commentary on Plato’s Phaedrus by Hermias of Alexandria, who lived in the 5th century CE, as an exegesis of a specific passage of Plato’s written text (Phdr. 275c). Either way, the anecdote distills the myth of the Academy and disseminates the idea of Plato as the dynamic professor of philosophy for his students and as an influential author for future generations of scholars and philosophers.

If we return, however, to the passage in Plato’s Phaedrus that generates this anecdote, we may find a potential middle-ground between these two models for the Academy, one that seems to by-pass Plato’s professorial authority as either teacher or author. The idea of writing a lesson in the soul is first raised in the Phaedrus when Socrates tells the myth of the invention of writing by the Egyptian god Theuth and its criticism by Thamus. Socrates prefaces the myth by describing it as ‘the tradition heard by our forefathers’, adding the caveat that ‘only they know its truth’. While it may have been the ensuing discussion of the myth by Socrates that forms the lesson that Plato’s student took to heart, it is equally possible that the anecdote highlights the myth as a form of discourse that somehow exists between Plato’s written dialogue and his oral lecture.

While scholars have debated the philosophical content of Plato’s myths (e.g. how the myth of Er relates to themes of justice and the good in the Republic), they often agree how myths highlight the process of transmission of philosophical lessons (e.g. the myth of Athens and Atlantis in the Timaeus-Critias or the myth of Diotima in the Symposium). Could this anecdote offer tantalizing evidence for the use of myth in the curriculum of the Academy and for a scene of teaching that operates somehow beyond the authority of Plato the teacher and author?

It is this question that is the basis for the project and exhibition Myths of the Academy. On receiving one of the generous Ronald and Deborah Ratner Distinguished Teaching Awards in 2014, I set about developing a project that substantially expanded my exploration of the dynamic between Classics and Contemporary Art as a pedagogic environment for my students at Ohio State. I am a firm believer in the uncanny power of artists to break down academic stalemates. By taking what they find interesting and works for them for their own creative practices and research, artists can offer unexpected and often radical proposals in their research. This project came hot on the heels of my collaboration with the artist Paul Chan and his positing of a hypothesis of art’s inner law of cunning via a new reading of the controversial Platonic dialogue Hippias Minor. I also had in the back of my mind the upcoming exhibition about the legendary Black Mountain College at the Wexner Center for the Arts in the Fall (Leap Before You Look).

This context generated the basic framework for the project that took the question about the potential role of myth in Plato’s Academy and expanded it to specific role of the artists in the contemporary research university and the idea of art school in general. I invited a group of four artists and teachers (Dani Leventhal, George Rush, Suzanne Silver and Carmen Winant) to read and think about Plato’s myths with me in a series of reading groups. The four artists in turn invited a collaborator (Brett Price, Liz Roberts, Ryland Wharton, Geoffrey Hilsabeck) who would work with them on the broader questions of art, research and education. Each set of collaborators (Dani/Brett; George/Liz; Suzanne/Ryland and Carmen/Geoffrey) would then produce works for an exhibition that I would curate in Hopkins Hall Gallery. Then students from my Classics 2220: Classical Mythology class would be set an assignment that required them to engage with the Myths of the Academy exhibition.

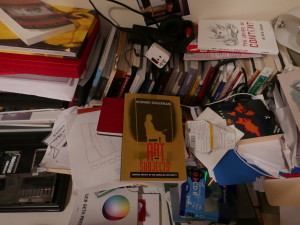

This was the plan. However, having set up the project in this way, during the first few Plato reading groups, working through our textbook Plato: Selected Myths, it became clear that we were in danger of replicating the problem of authority inherent in the anecdote about Plato’s student. As a Classicist asking artists to engage with Plato’s weird and wonderful myths, I seemed to be replicating the model of Plato in the Academy. What had happened to the role of myth as a means by which the authority of the professor could be challenged and transcended? Besides, who wanted to play Plato? I would rather be John Rice! As the project continued, however, the conversations moved further away from the myths and their interpretation to explorations of artistic research, art schools and art education. We read passages from Howard Singerman’s influential book Art Subjects and a recent roundtable discussion in Artforum about the crisis at the USC Roski School of Art and Design. After these sessions, I didn’t go back to my Plato, but went on to discover Frances Stark! Furthermore, as the artists’ projects developed, their own formations and practices guided the discussion of the ancient stories. Finally, in our last meeting, we continued our discussion in a Hopkins Hall studio space, using the process of drawing to articulate and communicate our own ideas about the myths and the artists’ works for the (fast-approaching!) exhibition. The reading group, which started out privileging the Platonic text and the Classicist as teacher, had now turned into something approximating myth as a means of transmission in a collective pedagogic endeavor.

At the same time as this shift was taking place in the reading group, it was also happening in the process of creating this catalog as well. In working on this essay, I was researching the physical topography of the Academy. I was intrigued by the possible connections between myth and the pre-Platonic site of the school – e.g. the way the myth of the hero Academus was used as a symbol for searching for philosophical truths by the Roman poet Horace, and the possible connection between the altar of Eros and the statue of Prometheus in terms of their role in myths (of the origin of virtue in the Protagoras and that of love in the Symposium). I had, furthermore, become fixated on the diagrams used to illustrate the mythic narratives in our Plato: Selected Myths book, from the whorls of the spindle of necessity in the Republic to the map of Atlantis from the Timaeus-Critias. This conjunction between fictional diagrams and historical topography lead me to invite designer Kelly McNicholas to create a logo for the project that conflated the concentric circles of the map of the mythical island of Atlantis with the position of the Academy in the North-West corner of a map of ancient Athens. Furthermore, this logo grounded the design of this two-part catalog (this volume by the ‘faculty’ and the forthcoming volume by the ‘students’), wherein for the former we have the juxtaposition of images and narratives of the artists, documenting their collaborations and research, and in the latter, the personalized images and narratives created by the students, accompanying their installation views of the exhibition.

In what follows in this volume and in the exhibition you will encounter a space filled with myths of the academy that embody collaborations, conversations, research and creativity. You will dream of an idea for a new ‘model’ art school (Carmen Winant and Geoffrey Hilsabeck) before descending into a dialogue of contested readings of Plato’s myths about love and the afterlife (Dani Leventhal and Brett Price). From there you will enjoy the playful tales and scenes of pedagogic context and community (George Rush and Liz Roberts) and pay attention to the knotty juxtaposition of words, ideas and their attendant errors (Suzanne Silver and Ryland Wharton).

But throughout this journey, you will not be lectured to, nor given a road map, instead you will be invited to experience Myths of the Academy as a collaboration of teachers and students, scholars and artists. In the words of my philosophus Platonicus Apuleius: ‘reader, pay close attention and you will enjoy’ (Met.1.1).

Footnote added June 14, 2024

Dear Angela, thank you for your reply & your image. I will send a more measured – or at least a more elongated! – response in due course. But what I immediately wanted to tell you is the reason that I shared that particular passage of Ali Smith’s Companion Piece (which I have just finished re-reading) was because what could be called (following the phraseology of Jacques Derrida) its ‘scene of teaching’. On hearing your frustrations & uncertainties about being within academia, I read Smith’s exchange about the ee cummings poem (who she basically denounces in the next chapter as a misogynist, racists & McCarthyite – reminding me of Philip Larkin, a poet I hate to love closer to home for me), as an alternative academy that opperates within the formal academy. While we hardly know each other, I get the sense from the care emanating from your work that there must be (& will be to come) moments when a student is speaking with you & even though you are both pressured & alientated by the structures that have placed you in dialogue, the dialogue itself is liberatory. Could this be a reason to remain? Could this be a reason to leave? Either way, our post-Minus Plato dialogue continues, here & elsehwere, that both began with (& didn’t begin only with) your letter to Paulina as a letter me (was it ever to me? or to a you as reader to come? I have been meaning to ask) & my response in the article ‘Companion, Peace’, from Experiments in Art Research: How Do We Live Questions Through Art?, edited by Sarah Travis, Azlan Guttenberg Smith, Catalina Hernández-Cabal, Jorge Lucero. More soon & in the meantime, hold tight! Richard

Pingback: Broken Records of the Colonizer: Dani Gal’s Collective Hauntology – The Minus Plato Archive