There is no original text, no “right,” perfect, whole object; we only have a broken bit of ceramic, mediated by centuries.

This is how Page duBois, in her book Sappho is Burning (complete with a Nancy Spero work on the cover), describes the potsherd that contains what we know of as Sappho fragment 2.

Here is Anne Carson’s translation:

]

here to me from Krete to this holy temple

where is your graceful grove

of apple trees and altars smoking

with frankincense.

And in it cold water makes a clear sound through

apple branches and with roses the whole place

is shadowed and down from the radiant-shaking leaves

sleep comes dropping.

And in it a horse meadow has come into bloom

with spring flowers and breezes

like honey are blowing

[ ]

In this place you Kypris taking up

in gold cupe delicately

nectar mingled with festivities:

pour.

And here is the potsherd:

|

|

1. PSI XIII 1300

11 x 14.5 cm

2nd century BC |

In reaction to the verdict of the legendary Oxbridge Classicist Denis Page that the writer on the object must have been ‘either very careless or ignorant or both’, duBois expresses gratitude to the ‘unknown writer who used a piece of pottery broken off from a whole, a vase, painted or not, used by women perhaps to carry water, or by drinkers at a symposium’. duBois’ portrait of this unknown writer allows for the possibility that she is either a woman or a man, the former scribbling the lines from a vessel she’d just broken while carrying it home, the latter in a drunken stupor amid a night of revelry. In either case, the potsherd reminds us that Sappho’s poetry has a tangible and material presence as an object, even beyond the scraps of papyrus that are often used to present its fragmentary state. Given this, it is no surprise that amid the contemporary artists who engage with Sappho’s poetry, the drawings and scrawled paintings of Cy Twombly and Julie Mehretu (who collaborated with duBois on an amazing artist-book of Sappho’s poetry), are also joined by sculptures and other objects that are no less engaged by the fragmentary nature of her poetry.

|

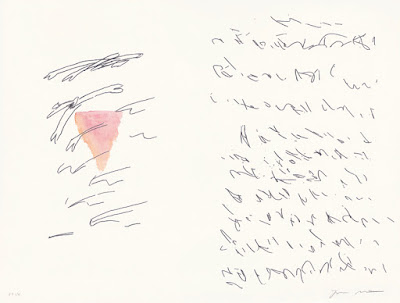

| Julie Mehretu Sapphic Strophe 3, 2011 from Poetry of Sappho Arion Press. |

Consider one of the contemporary sculptures on the beach of Skala Eressou, the seaside village on the island of Lesbos and the birthplace of Sappho.

Perhaps closer to duBois’ narrative about the origin of the poem scrawled on a shard of ceramic is the late work Sappho by Anselm Kiefer. An objectified realization of one of his famous series of works Die Frauen der Antike in the mid to late1990s, Kiefer has described his recent work as ‘a monument to all the unknown women poets’.

|

| Anselm Kiefer Sappho, 2002-2005 |

Both the Skala Eressou and the Kiefer sculptures bring together the poet and her work through the combined representation of the page and the body. Yet in doing so the broken page or the pile of books is supported by a rather simplistic conception of the perfection of the female form, whether through the silhouetted seated figure of the Skala Eressou work or the disembodied extravagant dress of Kiefer’s composite work.

Perhaps we need to look for less direct representations of Sappho in contemporary objects to encounter this combination of fragmentation and perfection that does not rely on the latter being projected onto some simplistic idealization the poetic genius embodies in the feminine form.

Such an indirect ‘representation’ of Sappho is offered by the work Volumes – inncompleteset by Paul Chan, initially presented at dOCUMENTA(13) and then in its complete form at his expansive solo exhibition at the Schaulager last year. Comprised of hundreds of gutted book-covers, flattened to make rectangles and painted with small square paintings of landscapes, Volumes – incomplete set is displayed in an incredible, ordered display that makes the viewer attempt to make connections between image and text, book-title and landscape.

|

|

| Paul Chan Volumes – inncompleteset, 2012, dOCUMENTA(13), Kassel, installation view and detail |

In an interview on the dOCUMENTA(13) website (the link is here), Chan describes how this particular work explores the perfection of incompleteness, and specifically how every ‘thing’ is not a ‘thing’ because it only exists as a network of relations to other ‘things’. In describing the perfect incompleteness of Volumes, Chan makes an analogy with Sappho’s poetic work. Nowhere in Chan’s work does the broken perfection of Sappho’s work become split between literary achievement and female life, but, like duBois, Chan’s Volumes – inncompleteset celebrates the persistence of her work as a complete thing, in relation to other things, in all its and their broken perfection.