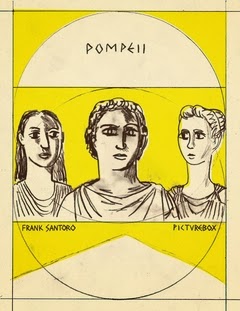

A browse through the Store at the Wexner Center for the Arts here in Columbus, Ohio, never fails to inspire me in my ongoing education in the weird and wonderful world of contemporary art, and also with topics to post on Minus Plato. The latest is Frank Santoro’s Pompeii, which is a brilliant graphic novel set in the days leading up that fated day in 79 CE, that ostensibly tells the tale of Marcus, an assistant to a well-respected painter, Flavius – their work and the women in their lives, as well as their divergent fates when Vesuvius erupted.

Yet this is not your typical representative of the Classics and Comics genre. On reading Santoro’s Pompeii it quickly becomes clear that this is a work that is deeply engaged with an issue that this blog is especially interested in exploring: the use of antiquity to explore debates in contemporary art. Santoro’s choice of Pompeii as a setting is multifaceted, and I only want to dwell briefly on one aspect here, as outlined by Santoro in his blog:

There is considerable scope for a discussion of the retelling of the dynamic between Marcus/Santoro the lowly assistant and Flavius/Clemente the celebrated painter in Pompeii, but here I want to highlight the idea that the ‘mash-up’ of Santoro’s ‘classical influences’ is in some ways inspired by Clemente. Two of the paintings that play a role in Pompeii are of Flavius’ mistress, called simply ‘the princess’ and his wife Alba. The former is a full-figure, reclining, while the latter is a close-up, head-shot portrait. In 2006, Clemente painted a series of portraits of well-known figures (e.g. Salman Rushdie), as well as his wife – Alba Clemente – which bears an uncanny resemblance to the head-shot portrait of Flavius’ wife, Alba.

|

|

However, back in 1997 Clemente produced a portrait of his wife in the position that Santoro has his painter paint his ‘princess’ as well.

|

| Francesco Clemente Alba 1997. Oil on linen. Courtesy |

The interplay between Flavius’ portraits of two different women and Clemente’s two portraits of his wife is actually made explicit by Santoro in the following ‘scene’ in Pompeii. When Alba arrives unexpectedly during a sitting by the princess, Flavius calls on Marcus to help not only switch canvases (the reclining portrait of the princess with a landscape), but also hide his model and lover, the princess herself. And where does Marcus hide the princess? Behind a frontal portrait of Alba, one which we will find Flavius working on later in the story. It is at the precise moment that the princess’ face appears from behind the portrait of Alba that Santoro seems to be evoking the interchangeability of Clemente’s two portraits. Yet a careful reading of Santoro’s Pompeii transforms the thinly-disguised biographical ‘fact’ of ‘the other woman’ into a meditation on artistic representation and issues of figuration and abstraction. Which one of Clemente’s Alba-portraits is closer to Alba Clemente? Or does such fidelity even matter?

For more on Frank Santoro, go here.

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful article. Many thanks for supplying these details.

Here is my web blog; visit website

Pingback: Las Materias Cubanas: José Manuel Fors between botany, literature and art – Minus Plato