Last night I attended a curious event at the Guggenheim Bilbao – a mesa redonda (roundtable) discussion of the exhibition Riotous Baroque: From Cattelan to Zurbarán – Tributes to Precarious Vitality – 3 days before the exhibition actually opens (this Friday June 14th). As a conversation between curator Bice Curiger and participating artists, Marilyn Minter and Cristina Lucas, the roundtable (originally planned for next week – June 18th) was, as a result, a rather surreal event, offering a laying-out of the curatorial rationale for and a very partial preview of the exhibition to come (including slides with installation photographs of galleries – tantalizingly close, but out of reach, a mere 3 floors above us in the auditorium). The person (whose name I don’t know) introducing the event was therefore charged with the unenviable task of making sense of such a premature discussion of a yet-to-open exhibition. She did a commendable job of making the best out of the situation by claiming that this timing was actually planned so as to offer an educational introduction that would prepare the audience for what they are in store for at the end of the week when they could see the galleries for themselves. Ironically, this spirit of priming the audience ahead of time did, however, seem to laugh in the face of the exhibition’s central theme of vitality. (Precarious indeed!) Anyway, this grumbling about appropriate ordering, structure, rigor etc is to be expected coming from a Classicist, right? So, let me get on with discussing the content of the roundtable and how it made me long for the exhibition to open on Friday.

The curator Curiger spoke first and commented briefly on the challenges of creating an exhibition that incorporated art works from different time-periods. She described it as ‘too banal to juxtapose according to motifs or formal analyses’ and thus wanted to find a ‘more complex, more direct, intelligent way to do it’. Here she was specifically opposing the idea of art history as style history – turning to the two artists to ask – ‘you don;t work within a style, do you?’ to which, they had to agree (although whether they did agree so completely as the curator would have been an interesting follow-up question). Then Curiger went on to emphasize the main theme of vitality and made an intriguing distinction between the 17th century works and the contemporary works by saying that it was really the latter that exuded a longing for vitality. Finally, with some installation shots, she talked about some of the juxtapositions between works – and here I want to wait until I actually see the show before I comment on her curatorial choices.

Onto the artists, first, Marilyn Minter discussed her idiosyncratic artistic process of photographing through glass and then laboriously painting with sticky enamel. She discussed how she made the below work, with the Kenyan artist, Wangechi Mutu, combining different negatives of the upper and lower lips.

|

|

Cheshire (Wangechi Mutu)

2011, enamel on metal, 60 x 96 inches

|

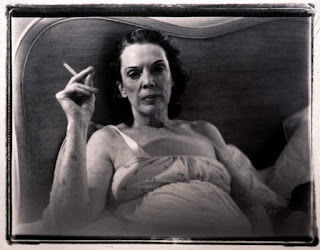

Minter then went on to acknowledge that her reputation as someone who explored ideas of ‘degenerative glamour’ in her paintings stemmed from her drug-addict mother, whom she photographed in 1969 in a series she only showed in 1995.

|

|

Coral Ridge Towers (Mom Smoking)

1969, black and white photograph

|

Then Curiger directed these comments by Minter towards the part of the show called ‘Vanitas, or the Manifestation of Excess.’

Following Minter, Cristina Lucas reflected on how Curiger had chosen from both her earliest works and her most recent for the exhibition. The earlier work, and the one that provoked most response from the rather subdued Guggenheim Bilbao audience, was a video-film called Mas Luz (More Light) (2003) in which the artist secretly records her conversation in the confessional asking the priest to explain to her why contemporary art and the Catholic church seem to be incompatible.

|

|

Still from Mas Luz (More Light), 2003

HD video 4:3 color and sound. 10 min

Edition 1/3 + 2 AP

Courtesy the artist and Juana de Aizpuru Gallery

|

The later work, called Hacia lo salvaje (Into the Wild) (2011) portrayed a woman (played by the artist) who consciously makes the decision to undergo the Medieval punishment of tarring and feathering, followed by exile from society. She emphasized how she saw it as a ‘very beautiful process’ when the decision to do this is taken actively as an escape from contemporary society and not as some barbaric punishment.

|

|

Still from Hacia lo salvaje (Into the Wild), 2011

HD video 4:3 color and sound. 16 min

Courtesy the artist and Juana de Aizpuru Ga |

The reversal of Medieval punishment into contemporary liberation seemed to me to parallel her earlier film in how it takes control of a form of stigmatizing oppression (enacted by, say, the Catholic church in the form of punishment of witches or the convention of confession). Furthermore, I also thought there could be an analogy to the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, in their attempt to escape Minos’ Crete through manufactured bird-wing contraptions. (I have quoted from the American poet Kinnel Galway’s poem ‘The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World’ for this post’s title as it nicely expresses the filth and cleansing aspects of the punishment and its appropriation for the Icarus myth).

Yet, it was my rather simplistic link to Icarus that provoked me to ask a question to the curator at the end of the session that has the potential to open out into a broader debate that I hope to explore in future posts. I asked Curiger why the explicit recourse to themes from Classical myth (e.g. the rape of Europa, Venus, the Bucolic etc) in the 17th century works (that from the press release I knew would be in the show) had been missing from the Contemporary works, especially given that other key points of reference e.g. religion (especially Catholicism) for Lucas and the degenerative glamour for Minter – had been shared by both periods? Her answer was very illuminating, so much so that even though it showed that she did not exactly understand my question, I had no interest in rephrasing it. Curiger said that unlike in the Renaissance, the artists of the Baroque were not collaborating with philologists and scholars to produce works. Instead, their workshops were more like laboratories for imagery to find out what motifs were popular in the market. The juxtaposition of the old and new (as in a form of film montage) seemed to be particularly popular. As for Contemporary art, Curiger continued, it is full of references to Classical Myth, you just have to make the connections yourself, it is up to the audience rather than the artist to lead them to these stories and themes.

As you can well appreciate, this answer was doubly-illuminating, not only for the exhibition, but also for what I am doing here in this blog and elsewhere in my research and collaborations with artists. If, as Curiger noted earlier, the Contemporary works show a longing for vitality, her comment about the audience’s role in making analogies with Classical myth in the more elusive recent work (rather than the trial and error of the Baroque mash-up of Classical themes) could be included as part of this longing or striving. Yet instead of vitality, this longing could even be for something that may be described as opposite to what we could understand as vitality (in its materialist, corporeal sense) i.e. for a certain intellectual or, dare I say, academic framework within which their work can be understood. Obviously this is not necessarily an art historical framework (a revitalized style history, as it were), but a more general ‘horizon of expectations’, in which other disciplines – e,g. Literature, Philosophy, Political Science – can engage with these works of visual art.

Furthermore, if we conflate this conception of longing for vitality and intellectual framework, we can appreciate how important works of Classical Literature are in bridging these ideas. For example, to return to the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, we see the incongruity between the scientific rationality of Daedalus in the creation of the wings as following nature, but at the same time a turning of his mind to ‘unknown arts‘ (ignotas…artes, Ovid Metamorphoses 8. 188). A comparable incongruity seems to be at work in how at the roundtable both the curator and participating artists in Riotous Baroque maintained the distinctions between differing artistic and historical periods (e.g. artistic production and markets; degraded beauty, the Catholic church now and then) while at the same time longed for a thematic focus on (the longing for) vitality.

Now that that I have been primed and educated at the roundtable, I am longing to see the exhibition in the flesh!