The presentations on the topic of ‘Origins & Creation’ in my class Classical Mythology/Contemporary Art were delivered on the following art works.

Peter Fischli & David Weiss The Way Things Go, 1987

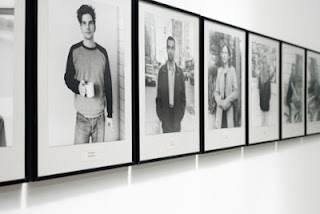

Hans-Peter Feldmann 100 Years, 1996-2001

Alighiero Boetti Map, 1989

Sheela Gowda And Tell Him of My Pain, 1998-2001

Vija Celmins Untitled (Ocean), 1990-1995

Damian Ortega Cosmic Thing, 2002

Emily Jacir Where We Come From, 2001-3

Simon Starling Wilhelm Noack oHG, 2006

Rachel Harrison Voyage of the Beagle, 2007

Micol Assael Chizhevsky Lessons, 2007

|

| Alighiero Boetti Map, 1989 |

|

| Hans-Peter Feldmann 100 Years, 1996-2001 |

In spite of the Ovidian creation being the most appropriate Classical model for the creative processes of both Boetti and Feldmann, we can still find traces of the Hesiodic creative model in discussions of the work and statements of contemporary artists.

|

| Vija Celmins Untitled (ocean) 1990-1995 |

Celmins’ statement collapses the two ‘surfaces’ (of the paper and the ocean) into two ‘images’ (again, of the paper and the ocean), but there is considerable ambiguity as to what she is referring to when she describes what ‘really isn’t there’. Is it the ‘image’ of the ocean that is ‘not there’ (i.e. it is merely a representation)? Or is it the paper (as surface or image) that is somehow replaced by the creation of an image of the ocean onto it? Either way, unlike Boetti’s Map or Feldmann’s 100 Years, Celmins’ Untitled (ocean) does not simply rely on a creative process of ‘re-ordering’ of a ‘world that already is as it is’, but instead isolates the moment of creation – the coming-into-being – at the heart of the creative and artistic act.