It just so happened that a day or so after Vladimir Umanets (aka Wlodzimierz Umaniec) ‘defaced’ one of Mark Rothko’s 1958 Seagram murals at the Tate Modern in London, I taught the latest Classical Myth/Contemporary Art class on the topic of Objects vs. Ideas: Conceptual Art. While I had the below list of artworks to talk about, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to engage with this topical art-world event as well.

Michael Asher Untitled, 1988

Martin Creed Work No. 127 The Light Going On and Off, 1995

Angela Bulloch Rules Series, 1993-present

Christopher Wool Untitled, 1990

David Wojnarowicz Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, 1991

Dayanita Singh Sent a Letter, 2008

Huang Yong Ping The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987-1993

Steven Parrino Skeletal Implosion #3, 2001

Tomma Abts Meko, 2006

While offering an explanation of a particular aspect of conceptual art – as typified in the famous statement of American artist Douglas Huebler: ‘the world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more’ – I brought up Umanets’ ‘work’. I told the students what had happened and read to them the statement following the incident in which Umanets denied ‘defacing’ Rothko’s canvas, but claimed instead to have ‘added value’ to it: “I believe that if someone restores the [Rothko] piece and removes my signature the value of the piece would be lower but after a few years the value will go higher because of what I did”.

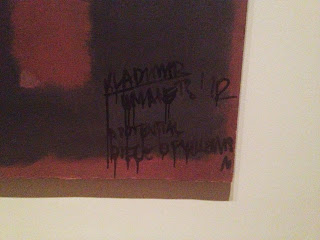

Now, given that my students were understandably skeptical about the value of Umanets’ work, in an attempt to invite them to think harder about its status as conceptual art, I asked them to consider the effect, not only of the action (i.e. the act of tagging or ‘defacement’), but also that of its content (i.e. the signature and what else it said). As well as signing his name, Umanets wrote: ‘a potential piece of Yellowism’, which, unlike the signature, provokes a chain-reaction of questions: what is Yellowism? how does it relate to the colour yellow? how can this work Black on Maroon possibly be considered ‘potentially’ yellow? and so forth. It is precisely this series of questions and our attempts to answer them through some manner of investigative inquiry that I asked the students to think about in terms of how conceptual art operates. However, in response to this suggestion, one of the students retorted by asking: if this provocation of an audience to a process of inquiry is the ‘point’ of Umanets’ action, did he really need to ‘deface’ another artist’s work in order to do so? Surely, there must have been another way he could have initiated this process?

It was in responding to this student’s valid and thoughtful question that I came up with a possible parallel from the Classical myth reading that we had been doing in the previous classes: the opening of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.We had been comparing Ovid’s creation myth to that of Hesiod’s Theogony and I was at pains to point out to the students that we cannot see the beginning of both of these poems in the actual origins of the cosmos, through figures like Chaos or Gaia/Earth, but in the openings to each work: Hesiod’s Muses and Ovid’s Prologue. For Hesiod, the story of the birth of the nine Muses, after the nine nights of furtive, sweet love making of Zeus and Mnemosyne, and their impact on mankind, both in terms of poets and politicians, is overtly programmatic for the poem to come on a number of levels. For Ovid, however, aside from the focus on transformation and the universal ambit of his poem, there is a more subtle programmatic statement contained in the following obscure phrase (Met. 1. 2, in the translation of David Raeburn – Penguin 2004):

Inspire me, O gods (it is you who have even transformed my art)

Here Ovid is making two – related – points. First, he is referring to the present moment at which his verse becomes a hexameter (6-feet), while previous (as he was writing in elegiac couplets) it would have been a pentameter (5-feet). At the same time, Ovid is also asking his reader to recall a moment in his poetic past when, in (possibly) his very first published poem – Amores 1.1 – the crafty god of love, Cupid – stole one of the ‘feet’ from his verses when he was hoping to sing about ‘weapons and violent wars’ (Am. 1. 1. 1).

Now, I saw in Ovid’s Prologue how one and the same gesture – the gods transforming his verse now and Cupid’s transforming it previously – could offer a comparable way of answering my students question of why Umanets’ needed to ‘efface’ Rothko’s work as a means of pointing to his artistic movement of Yellowism. For Ovid and Umanets, the signature and the reference collapse into one process. No more can we separate Ovid’s announcing that the gods have changed his art than we are being asked to recall such a process of change in his earlier poetry. Similarly, we cannot know if ‘Yellowism’ would have become known if Umanets‘ had not signed Rothko’s work.

Finally, and this is perhaps the most important part of my response, both present moments, both nows – the act of ‘defacing’ the Tate’s Rothko and the opening of the Metamorphoses – are precisely acts of ‘defacement’ by an external reference (to Yellowism and to Ovid’s earlier erotic poetry) that warns of a future contamination to come. In other words, for Ovid, even though he is writing in the epic meter of hexameter and even though he will be telling tales of the origin of gods and mankind up to the rule of Augustus, his poem will be haunted by the previous shift from erotic to epic verse. And, as any reader of the Metamorphoses can appreciate, this is precisely what happens – from the ‘first love’ of Apollo to the myth of Pygmalion. Like the question of the gender of the prophet Tiresias, who Ovid tells us in Book 3, had the opportunity to experience life (and sex) as both a man and a woman, Ovid’s poem will proceed without a clear generic identity – neither love poem nor epic, but both. Just so, as Umanets predicts (albeit in more blunt terms of market value), even if his ‘work’ is erased (i.e. effaced), we will not be able to view the Rothko without recalling it; its value has been increased and it has realized its Yellowist ‘potential’.

And again: yellowism is not an artistic movement. The incident in Tate is more artistic rather than yellowistic in its character. "Interpreting yellowism as art and being about something other than just yellow deprives yellowism of its only purpose", "Yellowism can easily be seen as a kind of art or creativity; however, such thinking belies its true nature" – Lodyga, Umanets. Remember "Black on Maroon 1958 II" has been titled "A POTENTIAL piece of yellowism".

Thanks for the clarification re: yellowism. What's the latest from this non-movement?