Just before New Year 1932, Walker Evans (1903-1975), the iconic American photographer, set sail to Tahiti on a luxury schooner called the Cressida.

|

|

Walker Evans

Portrait of a Woman, Tahiti

1932, silver print, ca. 1930s, 6 1/2 x 9 1/4.

|

In letters sent from there, and on his return a few months later, Evans recounts how he found the boat-trip deadly boring, with only the conversation of the other passengers, whom he dubbed the ‘fleurs du capitalist mal’, for entertainment (J. R. Mellow (1999) Walker Evans, 149). Although he had with him pocket editions of Virgil (Aeneid?), Marcus Aurelius (Meditations) and Dante (The Divine Comedy?) – send-off gifts of his friend Lincoln Kirstein (B. Rathbone (2000), Walker Evans, 74) – the vessel also had a substantial library, some of the contents of which Evans’ notes in a letter to German artist, Hanns Skolle:

Library of George Moore, Beerbohm, Boswell, Conrad, Alice in Wonderland, Schopenhauer, Hardy, Ring Lardner, Dostoyevski, Andre Gide, Apuleius, Willa Cather, Samuel Butler, Hamsun, Shakespeare.

To Skolle, 1/1/32 from Walker Evans at Work (1984) 74.

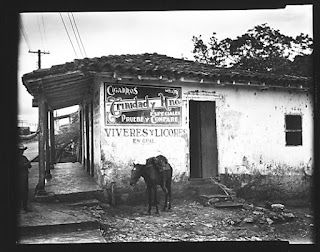

So, did Evans read Apuleius? Without scouring the extensive Walker Evans Archive, I am not able to find any references to Apuleius or The Golden Ass (which is the work we may presume was what he meant by ‘Apuleius’ in his letter, right?). If he did not, we may entertain the possibility that Evans’ inclusion of Apuleius in this cataloging of the ship’s library meant to display its esoteric nature, comparable to his placing the popular sports writer and satirist Ring Lardner alongside Shakespeare. Even if Evans didn’t read it, we could pass the time trying to work out which edition of The Golden Ass the Cressida library housed and possibly read by her other bored passengers: could it have been one of two cheap reissues of William Adlington’s 1566 translation by Abbey Classics (1922) or the Watergate Library (1923)? Or Gaslee’s revised version of Adlington for his 1915 Loeb? Yet if Evans did read Apuleius, where can we find ‘proof’ in his subsequent photographic output? One, immensely literal-minded approach, would be to see if Apuleius’ novel had an impact on Evans in terms of what he photographs. Does he, for example, see something of Apuleius’ Lucius in the donkeys of Cuba during his visit the following year (1933)? (Note the name of the store – echoes of Byrrhena’s atrium!)

|

|

Walker Evans, ‘Donkey Tied to Post Outside

“La Nueva Diana” General Store, Cuba’, 1933,

Film negative

6 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.

Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Another option would be to focus on how Evans takes his photographs as being somehow ‘inspired’ by Apuleius’ ass-story. For example, do not Evans’ 1938-41 hidden-camera, unposed portraits of New York subway travelers make you think of the escapades of Lucius-the-ass, especially his ability to see unseen and to hear (and retell) tales of adultery and depraved priests?

|

|

| Walker Evans Subway Portraits, New York City, 1938-1941 |

While both content (donkey-photos) and form (under-cover photography) approaches leave a great deal to be desired, perhaps a more satisfactory approach would be to attempt to conflate them by means of another aspect of Evan’s art: his own literary output. In a stream-of-consciousness short story written during the Tahiti voyage, initially called ‘A trip around the Island’ then later, with the wonderful title, ‘The Italics Are Mine’, there is a passage in which Evans’ narrator either says or thinks about what he dubs his (or his dubious interlocutor Buxby’s) ‘underdog past’ (for more on this passage, see Mellow (1999) Walker Evans, 156-9). Given Evans’ well-documented criticism of the pomp and wealth of the other passengers on the Cressida, instead of focusing on his photographic views of donkeys and donkey-eyed views, could we not instead imagine Evans reading Apuleius’ Lucius’ in terms of his retrospective narration of his life as an ass? Then we could compare Lucius’ recounting of his adventures, and especially his tedious conversations with the miser Milo with Evans’ satirical short story inspired by his own boring boat-trip amid his voyage of adventure to Tahiti. Such an approach to Evans’ Apuleius is potentially more interesting, not least because it may force us to engage with the political and cultural currents within Apuleius’ own work – the underdog African Platonist philosopher retelling a Greekish tale in (donkey?) Latin.