A two-part exhibition opened yesterday in Frankfurt called Jeff Koons: The Painter & The Sculptor – the former in the Schirn Kunsthalle and the latter in the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, until September 23rd. In both exhibitions, Koons offers his most sustained engagement with Classical Art to date with the his most recent work: the three-part Antiquity series (2010-2012) and two sculptures called Balloon Venus (2012) and Metallic Venus (2012).

In a video-trailer to the exhibitions (http://koons-in-frankfurt.de/videos/ – yes, another trailer for an artwork), we can see Koons express his wide-eyed excitement at having his work juxtaposed with the Liebieghaus’ extensive historical sculpture collection. He takes particular glee at having his Balloon Venus (2012) surrounded by Classical busts, singling out a bust of Apollo for particular mention and attention.

| Jeff Koons posing before his Balloon Venus (2012) |

|

| Jeff Koons admiring ‘Head of Apollo’ (‘Apollo of Antium’) |

In the same video-trailer, when discussing the painting side of the dual exhibition, Koons makes a revealing comment about his own artistic practice as well as how he sees his contribution to art history in general. He says he is excited about showing what he dubs ‘his history of painting’, in addition to his sculptures, making claiming that he was always a painter, even though he is most recognized as a sculptor. This comment is especially pertinent when we look at the Antiquity series of paintings, which seems to offer a painterly commentary on Koonsian and Classical sculpture.

|

| Jeff Koons Antiquity 1, 2010 oil on canvas 274.3 x 213.4 cm |

|

| Jeff Koons Antiquity 2 (Dots), 2012 oil on canvas 277 x 371 x 25 cm |

|

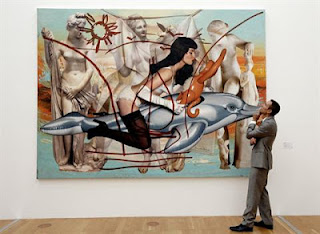

| Jeff Koons contemplating Jeff Koons Antiquity 3, 2011 oil on canvas 259.1 x 350.5 cm |

As a series, the Antiquity series shows a clear, developmental narrative. The reproduction of the sculptural group of Aphrodite fighting off a lecherous satyr with her sandal stands at the center of each painting, as does a superimposed scribbled sketch of a landscape with sun, sea and boat and a sugary landscape (pixelated into dots in the second in the series) act as a backdrop. The changes, however, occur on two levels. The first is the insertion of the female figure riding a dolphin and kissing a monkey, which reuses other of Koons’ sculptural works (the dolphin is that of Dolphin (2002) and monkey from Monkeys (Chair) (2003)).

|

| Jeff Koons Dolphin (2002) |

|

| Jeff Koons Monkeys (Chair) (2003) |

The dolphin riding female figure is, in fact, the actress Gretchen Mol, in the costume for her performance in the 2006 film The Notorious Bettie Page as part of a portfolio Koons made for The New York Times (http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/12/magazine/312style.html).

|

| Gretchen Mol as Bettie Page in Jeff Koons NYT portfolio, 2006 |

In a series of photos, Koons depicts Mol as Page cavourting with several of his sculptural pieces, not only the monkey and the dolphin, but also the iconic lobster that was central to Koons’ 2008-9 Versailles series:

|

|

|

As well as offering a commentary on Koons’ sculptures, as they have been reappropriated in the Mol photo-shoot, the second addition is that of the two Classical sculptures flanking the central one from the first in the series. Just as the re-employment of the Mol as Page with Koons’ sculptures of the dolphin and monkey tells a story behind the Antiquity series in terms of Koons’ artistic practice, so does the choice of the additional Classical sculptures. By adding the bronze priapic figure of the Satyr in the left and the crouching Venus taking off her sandal on the right, Koons is offering a dramatic prequel to the central figure of the goddess of love defending herself against the Satyr in the center. (The crouching Venus is leaning on a smaller statue, which is evoked in Koons’ sculpture Metallic Venus (2012) as well).

|

| Jeff Koons Metallic Venus, 2012 |

This drama continues in the third of the series, as, aside from the dotted background, the only perceivable difference between 2 and 3 is the replacing of a bronze priapic Satyr statue on the left, with the Mazarin Venus, from the Getty collection.

|

| Unknown, Mazarin Venus Roman, Rome, A.D. 100 – 200 Marble H: 72 7/16 in. 54.AA.11 |

Since the Mazarin Venus depicts the goddess alongside a dolphin, it is as if Koons’ own dolphin, and by extension Koons as well, has been inserted into the hallowed tradition of Classical art. Furthermore, by transferring the bronze satyr for the Cnidean-inspired figure of Venus, Koons’ depiction of Mol as Page is not merely a re-imagining of the extensive reproductions of the goddess of love, but is also making explicit the sexualized figure of the Cnidean Venus, as what Mike Squire in his excellent book The Art of the Body: Antiquity and its Legacy (2011), calls the ‘quintessential western ‘female nude” (p. 72). In many ways, Koons replaces the role of the Satyr in the central sculptural group with his role as an artist in his Pygmalionesque practice of using Venus-like models throughout his career, from Cicciolina in the infamous 1991 Made in Heaven series to Mol in the New York Time portfolio.

Does Koons’ Antiquity merit such close attention? Or should it be dismissed as cheap kitsch? In either case, it brings with it an informed (or at least informing) discussion of the legacies of Classical art that cannot be ignored.

For more on Jeff Koons, go to http://www.jeffkoons.com/