To the Reader

Dear Reader, as I write you this, author Lewis Hyde is giving a lecture at the Wexner Center for the Arts about his recent book A Primer of Forgetting. While I cannot be there in person (so close, yet so far), I want to use this post to send him a group of three related questions. If they happen to reach anyone in Columbus in time, please can you try to ask Mr. Hyde one or all of them? I know I am asking a lot, a miracle perhaps, but these questions cannot wait. These are urgent, impatient questions, which, I have to confess (why this language of confession?) are asked in anger. Mr. Hyde, you know something about impatience and its better-looking twin, patience. You wrote about this particular virtue in the preface to a recent edition of poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. You know how he ends one of his famous poems with the urgent imperative: You Must Change Your Life. (In asking these questions, I too am asking you to change your life, Mr. Hyde).

Black irises in my heart/and on my lips…flame./From what forest did you come to me/O crosses of anger?

In your preface to Rilke’s letter you mention the sculptor Auguste Rodin, about whom the poet also published a book and to whom he wrote a letter shortly after his letter to Krappus (the young poet). You quote Rilke’s letter to Rodin as follows:

[O]rdinary life…seems to bid us haste, [but patience] puts us in touch with all that surpasses us.

This homily to patience is invoked earlier in Rilke’s book on Rodin, which you quote as follows:

There is in Rodin a deep patience which makes him almost anonymous, a quiet, wise forbearance, something of the great patience and kindness of Nature herself, who…traverses silently and seriously the long pathway to abundance.

These two Rilke quotations – to and about Rodin – are both introduced by a reflection of your own about patience and Rodin. You write:

[T]hen begins the practice of patience, a virtue in which Rilke has been schooled by Rodin…

It is here that I ask my first, somewhat leading, question:

- Is this patient educator Rodin the same man as the renowned sexual predator currently on display in the Columbus Museum of Art exhibition Rodin: Muses, Sirens, Lovers, the basis of my continued protest in the form of my project Caryatids and the Patriarchy?

I have allied myself to sorrows,/I have shaken hands with banishment and hunger./My hands are anger,/my mouth is anger/the blood of my arteries a juice of anger.

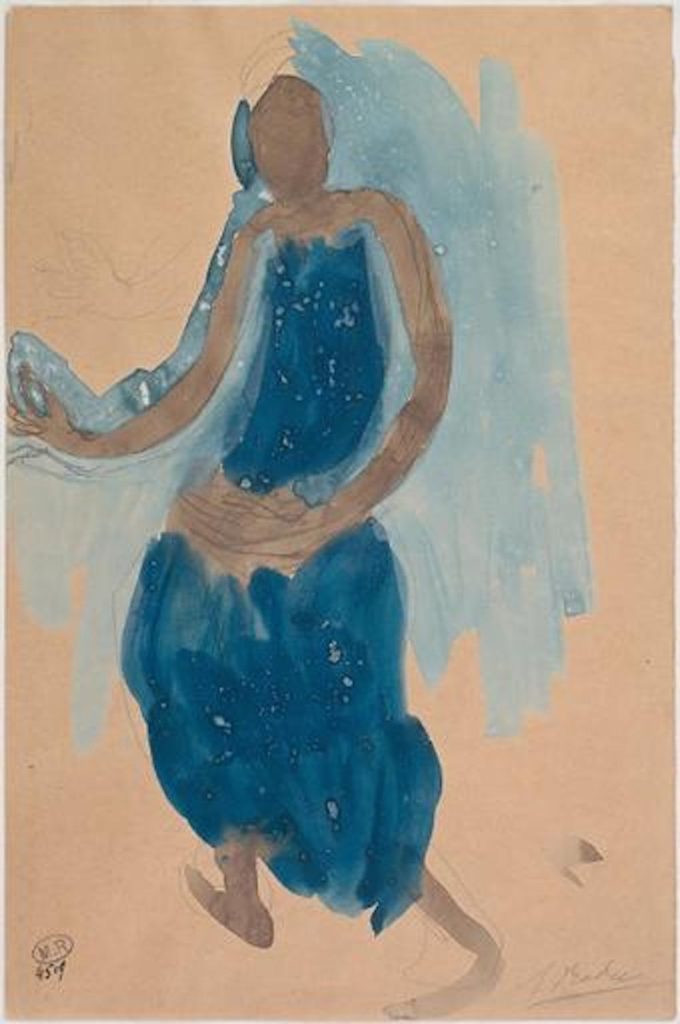

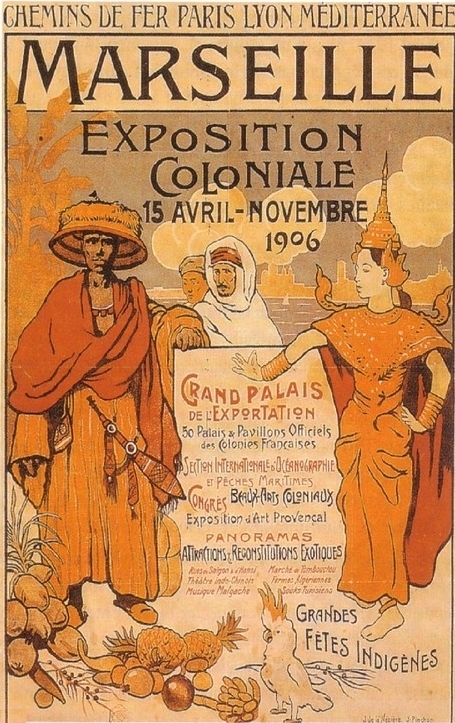

Maybe you just admire his sculptures and like Rilke distance yourself from the man. Maybe he wasn’t all that bad. Perhaps, when Rilke knew him he was more contained and less aggressive with women – his students and proteges like Camille Claudel or his models. But are not Rodin’s sculptures of women beautiful works of art? Surely a man cannot be judged for the failings of his age? But what were the failings of his age? In an online article Anna Blair (images from which illustrate this post) contextualizes Rodin’s drawings of Cambodian dancers within what she dubs the ‘Imperial Imagination’. She ends her article as follows:

Rodin’s sketches of Khmer dance immortalized the Cambodian Royal Ballet’s 1906 visit to France, capturing the excitement of French audiences, and ensuring that this encounter between colonizer and colonized would not be quickly forgotten. In utilizing the Cambodian Royal Ballet for his artistic ends, Rodin’s drawings, like the Colonial Exposition itself, are beautiful. But they testify to a long record of European efforts to aestheticize foreign cultures rather than a true engagement with Cambodia. While Rodin never completed larger projects based around the Khmer dancers, plans for the Museum of Living Artists show their continued impact. To Rodin, as to his compatriots, the Cambodian Royal Ballet seemed to be the direct descendants of a hazy and ever receding pre-modern world. In sketching the dancers, Rodin created his own colonial myth.

Now, Mr. Hyde, does this feel familiar? You must recall in your book The Gift how you described the potlatch as a ritual of the past, of a ‘hazy and ever receding pre-modern world’? You must remember, because you call yourself out on it in the 2019 preface to the third edition where you tell the story of your conversation with Tlingit elder who wished that you hadn’t spoken of his people in the past tense. To be fair, you corrected this oversight in the new edition, with some considerable fanfare. However, did the elder’s point really sink in? Here, then is my second question:

2. Do you anywhere in your writing engage with the art of living Indigenous peoples?

In the same preface you refer to a film account of your book at depicts the Kwakwaka’wakw artist Wayne Alfred (whose works also illustrate this post), but when you wrote your most recent book A Primer for Forgetting (which you discussed at the Wexner today – your talk must be over by now), in your multiple entries about visual contemporary art FROM THE MUSEUM OF FORGETTING, not one living Indigenous artist appears. So, in spite of your good intentions, your corrections of your tenses, how have you put pay to your own colonial mythmaking?

O my reader/do not ask me to whisper,/do not expect musical delight.

My third and final question needs no long and winding preamble. I must let my impatience get the better of me. And my growing anger. Mr. Hyde, can you tell me:

3. Why you never mention Palestine in any of your writings?

Here is where Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian poet of Troy, whose poem To the Reader (published at the beginning of The documenta 14 Reader) has been accompanying this post, must have the last word.

This is my suffering,/a wild shot in the sand/and another to the clouds.